Hours before dawn broke on August 19, 2020, Michael Flores sat in the front seat of a fire truck and watched a Boeing767 make a low pass 300 feet above Los Angeles International Airport (LAX). Around 2:30 that morning, the plane’s captain had informed air traffic control at LAX that his left wheel gear was malfunctioning and he might need to make an emergency landing. Hoping the firefighters on duty that night might be able to see from the ground what he, in the cockpit, could not, the captain decided to bring the plane in for a low-altitude flyby.

From his vantage point on the tarmac, Flores strained his eyes, trying to detect the wheel well—but he couldn’t see a thing. “Uh-oh,” said the firefighter sitting next to Flores. “This isn’t good.”

The Boeing 767, part of the FedEx cargo fleet, was en route from Newark, New Jersey. With all the freight on board it was pushing 750,000 pounds. And it was still dark outside.

To make matters worse, the aircraft was running low on fuel and had to land. Flores, a 30-year veteran of the Los Angeles Fire Department (LAFD), was at that point a relatively new member of the Aircraft Rescue and Firefighting (ARFF) unit—an elite squad of firefighters based at LAX whose core mission is to protect planes and their passengers and cargo from catastrophic fires.

Many years earlier, Flores recalled, a JetBlue flight headed from Burbank to New York had been forced to make an emergency landing at LAX with its front wheel gear stuck at a 90-degree angle to the runway; by the time the plane stopped, the front wheels had burned off and the landing gear was little more than a smoldering metal stump. In that case, the landing gear held long enough to bring the plane to a safe halt. But now, Flores wondered, what if there was no landing gear at all? A grim picture began to take shape in his mind, and he watched with growing alarm as the 767 made its final approach toward the 12,923-foot-long runway 25R, one of the longest in the United States. As the plane touched down, the left engine slammed into the tarmac. A trail of brilliant sparks lit up the darkness as the aircraft began to screech down the runway.

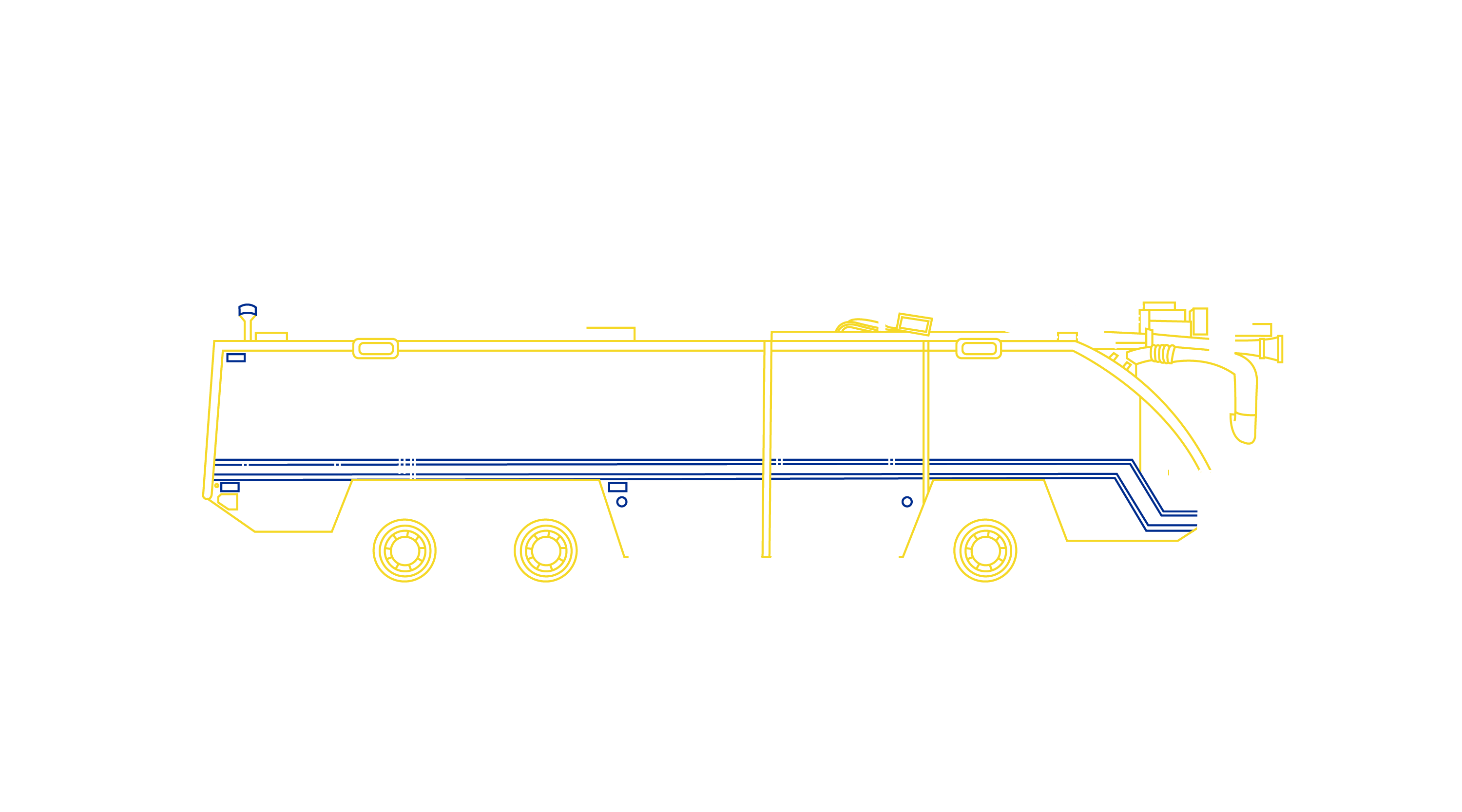

Flores and the rest of the ARFF team at Station 80 sprang into action. Six huge firefighting vehicles—$1 million lime-green behemoths called Panthers, custom-built for LAX by the Austrian firm Rosenbauer—had been prepped, and now they raced onto the runway. More than a dozen firefighters swarmed the plane. One team moved toward the cockpit with a set of movable stairs to extract the captain, who was unhurt. But on the other side of the cockpit, the first officer had already opened his window and tossed a knotted nylon rope to the ground. Yelling “Are we on fire?” he tried to lower himself to safety. Suddenly, his bare hands slipped off the rope, and he tumbled to the cement below, injuring his leg.

Watch them in action now.

In the end, the FedEx plane didn’t catch fire—but it very well could have. It was exactly the kind of nightmare scenario that Flores and the other members of the ARFF squad train for day after day: a calamitous wreck that could kill hundreds of people and cause billions of dollars in damage. Whereas other firefighting units in the vicinity—there are two other stations in close proximity to LAX—are tasked with running point on medical emergencies and fires inside the airport’s eight terminals, the members of Station 80 have just one core job: to help protect the roughly 700,000 planes that pass through LAX each year. Fuel spills, smoke in a cockpit, an unexpected or strange odor—seemingly small mechanical issues could in seconds become life-threatening conflagrations.

With such an immense array of potential threats, this elite crew is prohibited from leaving the airport perimeter. Instead, they patrol it relentlessly, navigating the mazelike corridors of runways, ready to intervene at a moment’s notice. “It’s a whole ecosystem,” says Captain Leonard Sedillos, a veteran firefighter whose mellow disposition belies a fierce commitment to his team. One of several fire captains who oversee Station 80’s operations at LAX, Sedillos watches over his teammates with the devotion of a mother hen.

Your whole career could be judged on just one incident.

Incidents don’t happen often, but when they do the response requires a precise combination of teamwork, equipment and experience. With such high stakes, it’s no wonder the ARFF team takes its work so seriously. Armed with the most up-to-date training protocols and the best equipment, the team is able to harness decades of experience in the most demanding environments in order to prevent the kind of mass-casualty disaster that could scar a city or a country for generations. Working largely out of sight, and with a focus on prevention as well as response, the members of the LAX ARFF squad are the tip of the spear in the daily fight to keep America’s airline passengers and cargo safe.

They spend their lives training for the thing that they hope never happens. But if it does, they are ready.

When night falls, LAX turns into a miasma of inky blackness; the only lights visible are those on the ends of a plane’s wings and occasionally in the nose gear.

For this reason, the firefighters have a rule book for driving around the airport. Special badges demarcate where people can and can’t go. On a recent day, a firefighter driving a Panther slowed down as he pulled into a curve to exit the tarmac. Top-heavy and laden with bulky machinery, the Panthers can reach 75 mph, but if driven incorrectly they can also topple while going 15 mph.

A single incident here at LAX can break like a wave, throwing the entire country’s air traffic control patterns into disarray for days. “If we have an incident and they have to close the runway for a little bit, it changes the system in the whole country,” says Flores. All of which gives the dance of the tarmac a heightened elegance. Admiring plane spotters flock daily (and nightly) to a nearby overlook on Imperial Highway just to watch it unfold. And yet despite the tension inherent to this ceaseless balancing act—or perhaps because of it—the airport is by and large an oasis of relative calm, free of the thrum of human chaos. It’s one of the reasons, in addition to Station 80’s bright lime-colored Rosenbauer Panthers, that these veterans refer to LAX as “the green world.”

His first assignment took him to LAFD’s Station 94, in the so-called Jungle, where he began to rack up stories. Like the time the survivor of a car collision came limping toward him with his foot dangling by a few spindly tendons beneath a protruding bone; or the 3-year-old girl who died in his arms, her warm blood soaking his gloves. As many firefighters do, Barnes deploys dark humor to help blunt the trauma. He’ll never forget the motor-vehicle crash in Venice Beach that killed multiple people, including a man whose body he discovered bent backward over itself three times.

They call the tumult outside “the red world”—a stream of homeless encampments, car crashes and police chases. “It’s horrible in the red world,” says Flores’s colleague, firefighter Billy Barnes, a self-described “airplane nerd” who clocked 21 years fighting blazes on the streets of L.A. before transferring to LAX in 2021. “All my buddies out there want to be in here,” he says. Born in Queens, New York, Barnes moved to L.A as a boy, graduated high school and then joined the Air Force, serving in Operation Desert Shield. After watching the regular beat of mayhem on the nightly news, he realized he wanted the action that city firefighters were seeing. “I’m gonna do that!” he said to anyone who would listen.

In the middle of 2021, Barnes landed at Station 80, where he plans to spend the rest of his professional life. He is the station's in-house amateur documentarian and historian. Barnes spends his off-time on various firefighting-related activities: building mock-up planes and runways for use in tutorials about safety and best practices; framing black-and-white photos of old fires and the people who fought them; or quietly erecting memorials to the worst aircraft crashes of the past, like the collection of photos that adorns the corner of the conference room, alongside a newspaper clipping that’s now 31 years old: “Pilots Dead, Many Missing in Fiery Los Angeles Crash.”

As big as these planes are, at night they kind of disappear

Fog turns the airport into a nearly impenetrable murk. Flores can remember nights when the only way he knew a plane was close was because he could hear the roar of the engines.

The crew are tasked with patrolling inside LAX Airport’s 3,000 acre perimeter - that’s the equivalent of around 2273 NFL fields.

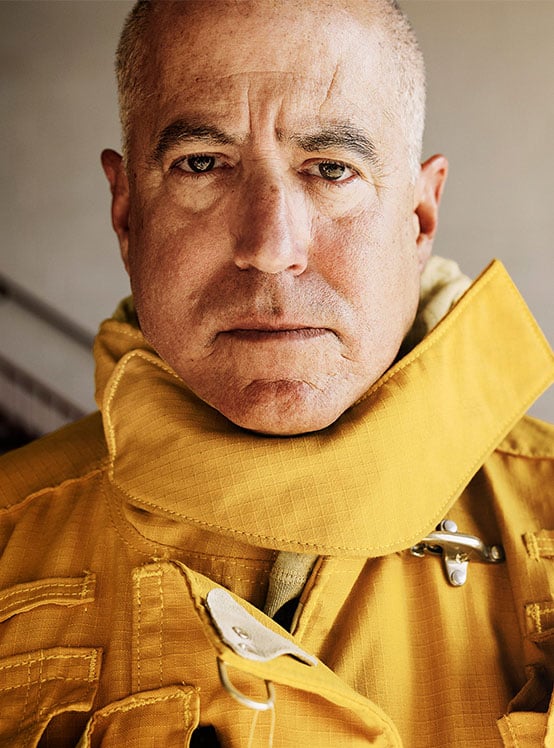

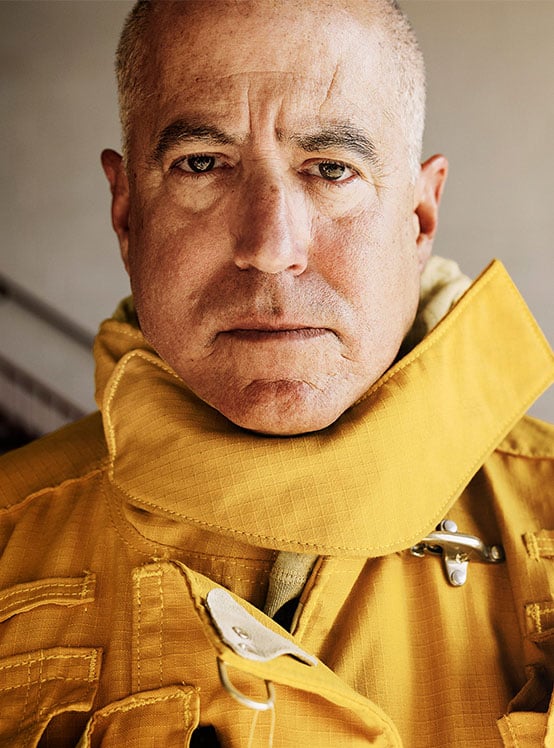

Michael Flores, a 30-year veteran of the Los Angeles Fire Department.

The ARFF squad trains obsessively for the disaster they hope never strikes at LAX. But if it does, they’ll be ready.

Tony Guzman was a rookie firefighter back then, with only three months under his belt. It was a February night in 1991, right around dinnertime, when the call came in. A major incident was underway at LAX. By the time his crew, which was stationed just outside the airport at the time, arrived, a giant plume of black smoke was curling skyward from the tarmac. Two other crews were already laying down fire-suppressing foam on the inferno that was consuming U.S. Airways Flight 1493, a Boeing 737-300 carrying 89 people.

Guzman was suited up already and was one of the first firefighters to breach the plane. He entered through a door just behind the cockpit and was surprised to discover a giant hole in the plane’s roof that had created a kind of tunnel through which hot gases and heat were escaping, leaving the rest of the plane’s cavity relatively clear. The fire was still blazing, however, and Guzman watched the flames move forward through the cabin toward the first-class area and the cockpit, where he was standing. He saw charred bodies burned beyond recognition “like mannequins,” the victims still seated, killed by smoke inhalation. Everyone else had either escaped or died—except for the pilot, who, though still alive and moaning, was close to death, crushed by the force of impact. For 10 minutes Guzman and his colleagues sawed through the plane’s thick metal, trying to extract him. But despite their efforts, the pilot could not be saved.

Watch them in action now.

Only then did Guzman’s radio crackle to life with more disturbing news: There had been another aircraft involved in the crash. Guzman and the other firefighters began digging through the wreckage, looking for signs of a second plane. Soon they found a small wheel and a propeller that clearly didn’t belong.

As they would soon learn, the U.S. Airways flight had rear-ended a smaller SkyWest Airlines commuter plane carrying 12 people and taxiing for takeoff. An air traffic controller had unwittingly cleared the smaller plane for takeoff on the same runway that the larger plane was using to land. Together, the two planes had collided with a small structure and caught fire. During the crash, the bigger plane crushed the smaller one, killing all 12 on board. All told, 35 souls perished that day—the single worst accident in LAX’s history.

Thirty-one years have passed since the 1991 crash, but the specter of the tragedy still looms. The work of preventing a repeat is a kind of quiet war; the enemy is the ever-present possibility of human error. Michael Flores spends hours logging and detailing intricate lists of equipment and inventory, making sure his colleagues have the tools they will need when disaster strikes.

Quiet and unassuming, Flores is a stocky, dark-haired native of East L.A.’s El Sereno neighborhood. He grew up just down the street from a fire station. In those days, engines were huge and noisy, and you could hear them “rumbling, rumbling” in the distance, he says. Today, they hum along like killer whales, silent and huge. When Flores was 17 years old and still a senior at St. Francis High School, in La Cañada Flintridge, located north of L.A., he participated in a student mentorship program at LAFD, working at the maintenance facility where tools and machinery were repaired. He began learning how to put ladders up and do hose-lays. Flores’s father was a diesel mechanic and ran his own business, and Flores felt comfortable around the oily machines and big engines of the trucks. His first real fire was a residential blaze in Boyle Heights, near downtown L.A. More than the fire itself, he remembers the “overhaul”—the cleaning up and taking stock of what remained. It left a vivid impression, “like a snapshot,” of loss. “It could have been my parents’ house,” he says. “You’re basically salvaging what’s left and covering stuff up.”

The cockpit of a Panther is filled with extensive tech for comms and firefighting.

For understandable reasons, the firefighters often skirt around the issue, but the subject of trauma intrudes. Barnes, for instance, recalls the July 6, 2013 Asiana Airlines crash at San Francisco International Airport, which killed three and injured 187 after the plane’s tail struck a seawall and the plane broke in two. Word got around that the firefighters on duty that day had tragically and mistakenly hit a survivor who had wound up on the tarmac and was covered in foam. An autopsy later determined she had still been alive at the time.

“When you hear about one of us finally taking our lives or going into a bad depression, those are guys who knew the decision they made wasn’t exactly the best one,” says Barnes. “That could very well happen here, but it’s not going to because we have a lesson learned.” Still—if you add in a collision with another plane, a strong onshore wind and a secondary vehicle, suddenly, the nightmare scenario that keeps Captain Sedillos awake at night begins to take a menacing shape.

The only hedge is training. One hot, cloudless day in November 2021, several members of the Station 80 ARFF team make their way 75 miles east to the fire station at San Bernardino International Airport for a mandatory “live fire burn.” A haze covers the nearby San Bernardino Mountains. Fire teams from countries around the world— Nigeria, Canada and Germany, to name a few—often come here to train.

On a vast cement tarmac, near two massive warehouses for FedEx and Amazon, sit many rows of decommissioned planes, waiting to be dismantled for spare parts. Behind a dun-colored single-story office building sits the stage for the day’s training: two empty plane shells wrapped in black paneling—mock-ups of the real thing. The larger of the two sits within a giant circular stone-filled pit 50 feet in diameter, equipped with 78 gas pipes. The firepit is connected via the underground pipes to a 30,000-gallon liquid propane tank.

On this day they’re spraying water, but in the event of a real fire they might use polyfluoroalkyl substances, or PFAS, sometimes called “forever foam,” a chemical fire suppressant that consumes vapor, the lifeblood of fires. In rare cases, they will deploy an expensive and highly toxic compound called Halotron, which is particularly useful for putting out cockpit fires without damaging sensitive electrical equipment like a plane’s auxiliary power unit. Each one of the six green trucks at Station 80 carries 3,000 gallons of water and 1,000 more of PFAS. Perched on top of each truck like a scorpion’s stinger is a roughly 60-foot-long extendable turret that can strike a hole through metal and puncture an airplane’s exterior, opening up a cavity that allows the firefighters to insert water or foam.

In addition to constant physical training, the LAX firefighters are continually learning about the complexities of aircraft. Airbuses are different from Boeings; commercial transporters from private jets. How many exit rows? How many seats and aisles? How accessible is the cockpit? Planes used to be made of aluminum; now they’re made of composites, whose behavior in a serious crash or fire remains a disconcerting unknown.

Every bit of knowledge can translate into faster action, and as Guzman tells his younger teammates over and over: Mere seconds make all the difference.

If the team is not ready for everything at any moment, people might die—the old, the infirm, the disabled first. And sometimes firefighters. While the training at San Bernardino is just that—training—it’s not without its risks. A few years ago, a firefighter had a heart attack while breaching one of the mock-ups used as part of a regular exercise. Luckily, his teammates saved his life.

Among the leaders of the group participating in the burn in San Bernardino is Captain Sedillos. Raised in a family of firefighters, Sedillos knew for a long time that he wanted to follow in his father’s footsteps. Back in his father’s era, firefighters didn’t have the sophisticated equipment they do now, like the three-layered suits with their names stitched in fluorescent type on the back and headscarves made of fire-retardant fabric. In the old days, you could tell a firefighter because often their ears were half-melted from excessive exposure to heat. They didn’t have breathing apparatuses or fireproof suits. They wore regular boots instead of the steel-toed kind that contemporary firefighters wear.

Two weeks later, I visit the crew back at LAX. Today, the mood is calm but ready. The times have changed, but the team Sedillos manages now remains a family. They work in shifts of 48 hours, which means that at the end of the day they’re spending a third of their lives with each other, inside the station. The firefighters take turns cooking during their weekly shifts. On this day it’s pulled pork sandwiches, fresh fruit and chocolate cake. “You can get lulled into a false sense of security because of creature comforts here,” says Sedillos. “A lot of what you’re doing is just having to be constantly prepared for the ultimate disaster.”

Flores, who played football in high school, finds comfort in the camaraderie. Barnes cracks jokes, his laughter lighting up the room, but like most everybody else here, he has saved lives, revived the dead, and cut survivors and dead alike from burning wreckage. “I wanted some and I got plenty,” says Barnes. “I’m staying here until the day I retire.” Outside, the planes come and go, the hum of jet engines fading into a pleasant background din.

Flores digs into his sandwich. “When somebody is calling us, it’s usually not just because they want to call us to say, ‘Hey, come on over and visit,’ ” he says. “It’s because they have an issue, and you get there to help them with whatever problem that they may have. It’s a good feeling.”

Guzman, one of the oldest members of the team, is ready for what might come. When Guzman talks to the younger members of the ARFF team, he often tells them that things won’t always work out the way they hope. He finds himself thinking back to that February day in 1991. “I know how important time is,” he says. “Every second really does count. Lives depend on it.” It’s a sentiment all these firefighters share. And it’s an obsession that makes LAX safe for another day.

You've read about them, now watch them in action below.

The Disaster Artists takes you inside Station 80.

Captain Leonard Sedillos, one of several fire captains who oversee Station 80’s operations at LAX.

With cutting-edge equipment, relentless training and an intense family bond, the elite firefighting team at LAX—one of the world’s busiest airports—is ready to act if the unthinkable happens.

Words: Scott Johnson

Photography: Jim Krantz

Watch them in action.

Even the most experienced members of the LAFD team from Station 80 participate in regular training with live fire.

It’s a sentiment all these firefighters share. And it’s an obsession that makes LAX safe for another day.

Watch now

Firefighter Eric Johnson during a quick break while training in San Bernardino.

LAX

fire department

Hover to explore the Panther

Hover to explore

The

disaster artists

Manufacturer

ROSENBAUER

Cost

$ 1,000,000

Made of

ALUMINIUM

Engine size

750BHP

Operating weight

40 TONS

Top speed

75MPH

Height

12 FEET

Length

38.4 FEET

Wheels

6

LAX Fleet

6 TRUCKS

Firefighters it can seat

6

Special feature

A 60 FOOT-LONG EXTENDABLE TURRET THAT CAN PIERCE AN AIRPLANE EXTERIOR

Water it holds

3,000 GALLONS

Forever Foam it holds

1,000 GALLONS

In a normal year, about 1,900 planes take off and land at LAX every day—more than one departure or arrival per minute. Many are large commercial jets; some, like the two-level Airbus 380, can hold several hundred people and more than 80,000 gallons of highly flammable jet fuel.

1,900

planes take off and land everyday at LAX

3,000

acres of land

200

foot-wide runway

700,000

planes pass through LAX each year

ARFF units have been around since 1937, when a U.S. Army Corps of Engineers team first demonstrated the firefighting capabilities of a high-pressure fog device, a revolutionary concept at the time. Later, in 1953, the U.S. Coast Guard ordered the first ARFF vehicle for use in the United States from a company called Oshkosh.

And so, much like soldiers, the team trains for the very worst. Collectively, these seasoned veterans have a few centuries’ worth of experience between them on city and metro crews across the greater Los Angeles region. But inside the nearly 3,000 acres of LAX, all of that experience is channeled into a narrow and intense beam. “It’s a whole different strategy in here,” says Flores, who joined ARFF in 2016 after 20 years in the city. “Coming here from the outside, it’s basically like you’re starting a new career.”

LAX, which served an astounding 88 million passengers in 2019, is a little like an island within Los Angeles, a city within a city. While the airport is managed by an entity called Los Angeles World Airports, the safety protocols and standards are set forth by the Federal Aviation Administration, whose tolerance for slippage and oversight is minimal to nonexistent. In the event of an incident, the FAA and the National Transportation Safety Board are immediately called. If all this sounds like a bureaucratic morass where multiple municipal and federal jurisdictions collide, that’s because it is.

Since then ARFF teams have been deployed around the globe. ARFF teams require months of specialized training in airplane layout and technology, night driving, fuel dynamics and special airplane firefighting protocols. A major incident involving an airplane is, thankfully, a relatively rare occurrence these days, happening only once every 20 years or so.

But these administrative entanglements seem to vanish the moment you set foot on the tarmac itself, a mesmerizing tableau of color-coded lanes and angles that hums like a carefully tuned clock. The airport runs on a tight schedule; there is a place for everything—and everything is in its place. The symmetry of runways, service roads and taxiways reflects this delicate dance. The weight of a passenger-less, fuel-less Boeing 747 is just over 412,000 pounds; fully loaded, it’s close to double that, and once the giants are moving, they won’t stop, even on a 200-foot-wide runway. A never-ending stream of cars, people, buses and fire trucks weave around, in front and behind them, taking care to stay out of their way.

But despite all these improvements in equipment, the ethos remains the same: duty, honor, community. Sedillos spent his childhood around his father’s station, where colleagues were family, sharing tragedies and successes alike. These days, Sedillos often finds himself pulling all-nighters

in both the “red” and “green” worlds. With his twin daughters in college, Sedillos’s overtime is helping put them through school.

Did you know?

Keeping LAX safe is no joke. The airport operates four runways and is one of the busiest in America.

LAX has a fleet of six custom-built lime green Panthers ready to spring into action at any moment.

The crew at Station 80 train hard to ensure they are constantly ready as more than 700,000 planes a year pass through LAX, that’s more than one departure or arrival per minute.

Lorem Ipsum

Did you know?

How heavy is an operational Rosenbauer Panther?

Around 40 tons, that’s roughly 48 of Max Verstappen’s RB16B 2021 Formula One cars.

A Panther can hold how many gallons of water?

3,000. The tanks are so big it would take around 48,000 8.4oz cans of Red Bull

to fill them up.

What engine size

powers a Panther?

The engine produces 750bhp. That’s similar to a typical NASCAR racecar.

Hover to learn more

Kevin Steward, who played basketball at USC, has been with the LAFD since 1998. Typically, only firefighters with many years of experience are accepted to join the elite team at LAX.

On cue, the pit bursts into flame as the day’s test engineers set it alight. Around the plane’s shell, a 20-foot wall of flame turns the air into a furnace, consuming the plane inside. Firefighters wearing fireproof suits and breathing apparatuses form a column six men deep and grasp a large hose connected to a Rosenbauer Panther. They advance steadily on the blaze, dousing it with huge arcs of water.

They spend their lives training for the thing that they hope never happens. But if it does, they are ready.

But every day at LAX presents a new set of challenges

For this reason, the firefighters have a rule book for driving around the airport. Special badges demarcate where people can and can’t go. On a recent day, a firefighter driving a Panther slowed down as he pulled into a curve to exit the tarmac. Top-heavy and laden with bulky machinery, the Panthers can reach 75 mph, but if driven incorrectly they can also topple while going 15 mph.

Tony Guzman was a rookie firefighter back then, with only three months under his belt. It was a February night in 1991, right around dinnertime, when the call came in. A major incident was underway at LAX. By the time his crew, which was stationed just outside the airport at the time, arrived, a giant plume of black smoke was curling skyward from the tarmac. Two other crews were already laying down fire-suppressing foam on the inferno that was consuming U.S. Airways Flight 1493, a Boeing 737-300 carrying 89 people.

Guzman was suited up already and was one of the first firefighters to breach the plane. He entered through a door just behind the cockpit and was surprised to discover a giant hole in the plane’s roof that had created a kind of tunnel through which hot gases and heat were escaping, leaving the rest of the plane’s cavity relatively clear. The fire was still blazing, however, and Guzman watched the flames move forward through the cabin toward the

first-class area and the cockpit, where he was standing. He saw charred bodies burned beyond recognition “like mannequins,” the victims still seated, killed by smoke inhalation. Everyone else had either escaped or died—except for the pilot, who, though still alive and moaning, was close to death, crushed by the force of impact. For 10 minutes Guzman and his colleagues sawed through the plane’s thick metal, trying to extract him. But despite their efforts, the pilot could not be saved.

You've read about them, now watch them in action below. The Disaster Artists takes you inside Station 80.

Click to learn more

Words: Scott Johnson | Photography: Jim Krantz

Click to explore the Panther

have landed whilst you have been reading this feature

9

planes

have landed whilst you have been reading this feature

16

planes

Did you know?

Click to learn more

Keeping LAX safe is no joke. The airport operates four runways and is one of the busiest in America.

The ARFF squad trains obsessively for the disaster they hope never strikes at LAX. But if it does, they’ll be ready.

Firefighters who defend LAX base their operations at Station 80 on the edge of the nation’s second- busiest airport.

Firefighters who defend LAX base their operations at Station 80 on the edge of the nation’s second- busiest airport.

have landed whilst you have been reading this feature

9 planes

planes take

off and land everyday at LAX

have landed whilst you have been reading this feature

16 plANes

acres

of land

You've read about them, now watch

them in action below.

The Disaster Artists takes you inside

Station 80.